Trees have played a significant role in human history, serving as symbols of growth, divarication, and infinite possibility. They have been used to represent intangible concepts, such as spirituality and knowledge, and have been a crucial part of communal identity and history. Trees have populated literature, art, and religion and have been used to perpetuate hierarchy and territorialization. They serve as witnesses and mnemonics of contextual support. “Arborescence”, as such, has a rich and varied cultural history and is used as a multidisciplinary term for any representation exhibiting tree-like qualities in its structure, growth, or appearance.

With this said, is it any wonder why Honorat Bovet turned to such an entity to champion his manuscript’s narrative?

A micro-taste of arborescence*

In Religion: Trees of Jesse

“Et egredietur virga de radice Jesse, et flos de radice ejus ascendet / And there shall come forth a rod out of the stem of Jesse, and a Branch shall grow out of his roots” (Isaias 11:1).

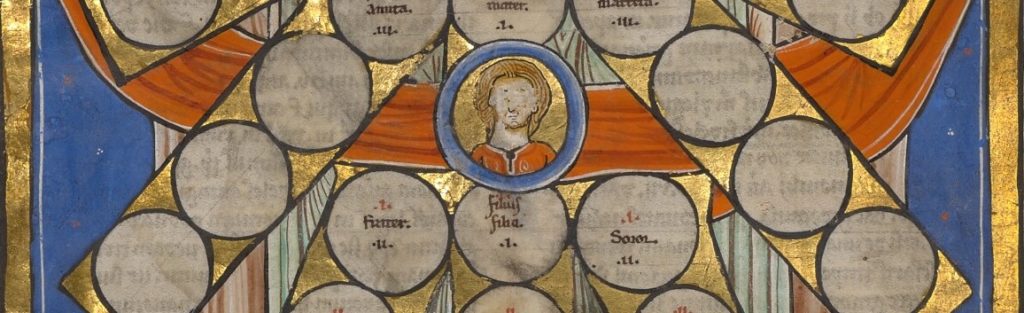

The Tree of Jesse iconography is based on the prophecy of Isaiah 11:1-2, which provides the textual basis for the genealogy of Christ through the Gospels of Matthew and Luke. The Tree of Jesse is usually depicted with an enlarged figure of Jesse reclined at the bottom of the image, with either a tree trunk or a thick vine sprouting from his side or navel that bears an ascent of branches with representations of his ancestors toward the top figure of Christ himself. The Tree of Jesse first appeared in the 11th-century Books of Kings and the Czech Vyšehrad Codex and soon became the most commonly produced Biblical image in medieval art. The Tree of Jesse established more than just a connection between man and God: it created a systematic ‘moralization’ of the tree in the medieval mind. Trees of Jesse were authoritative schematics that supported a theocratic campaign throughout the Middle Ages by championing the symbiotic protection of the “two swords” of Christ, the Church, and the princes.

In Government & Politics: Trees of Consanguinity

The genealogy of Christ traced to the Gospels of Matthew and Luke, as seen through the Trees of Jesse, led to the rapid expansion of Trees of Consanguinity. These trees (originally charts) portrayed marital rights based on Roman laws of inheritance adapted by the Christian Church. They were critical in mapping bloodlines when the notion of seven forbidden degrees of separation regarding marriage hit a boiling point in Gratian of Bologna’s Decretum ca. 1140. Trees of Consanguinity determined the legality of territorial inheritance, a foundation of domination. Acquiring natural spaces was crucial to nobility, and the Trees of Consanguinity justified one’s rule over a given area.

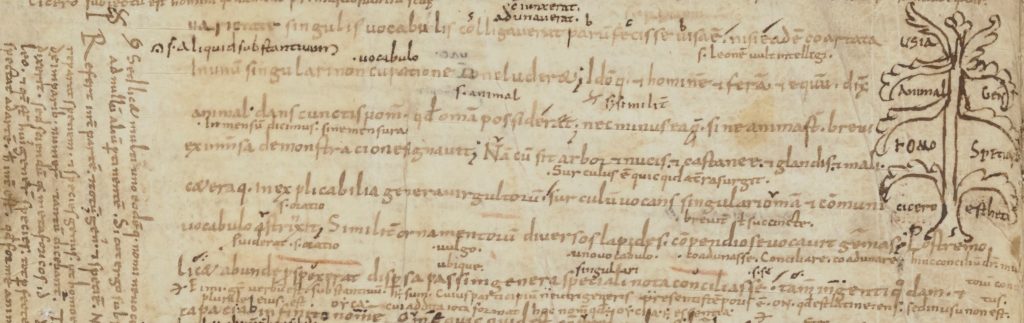

In Education: Tree Diagrams

Scholars who consulted encyclopedias like Isadore of Seville’s Etymologiae (compiled ca. 615-30 A.D.) used trees to organize knowledge, as revealed by surviving marginalia created by scholars to comprehend, organize, and memorize knowledge. A 10th-century manuscript from St-Germain’s library in Auxerre collected knowledge of reason, logic, and science. It included information from Aristotle’s Per hermeneias, Categoriae decem, Porphyry’s Isagoge, and Boethius’ Opuscula sacra. Scholars created diagrams in the margins to organize and memorize the information, including trees like the one on “f.31r” and “f.24v”, which contained the word “Usia” at the top of the tree-like structure, meaning “substance” in Latinized Greek.

*

For more examples, please view the project’s digital accompaniment on Twine.